Achieving universal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking water for all by 2030 is a target of the Sustainable Development Goals. Africa has been identified as being at risk of severe water scarcity. Nearly 400 million people in sub-Saharan Africa are denied even a basic drinking water supply.

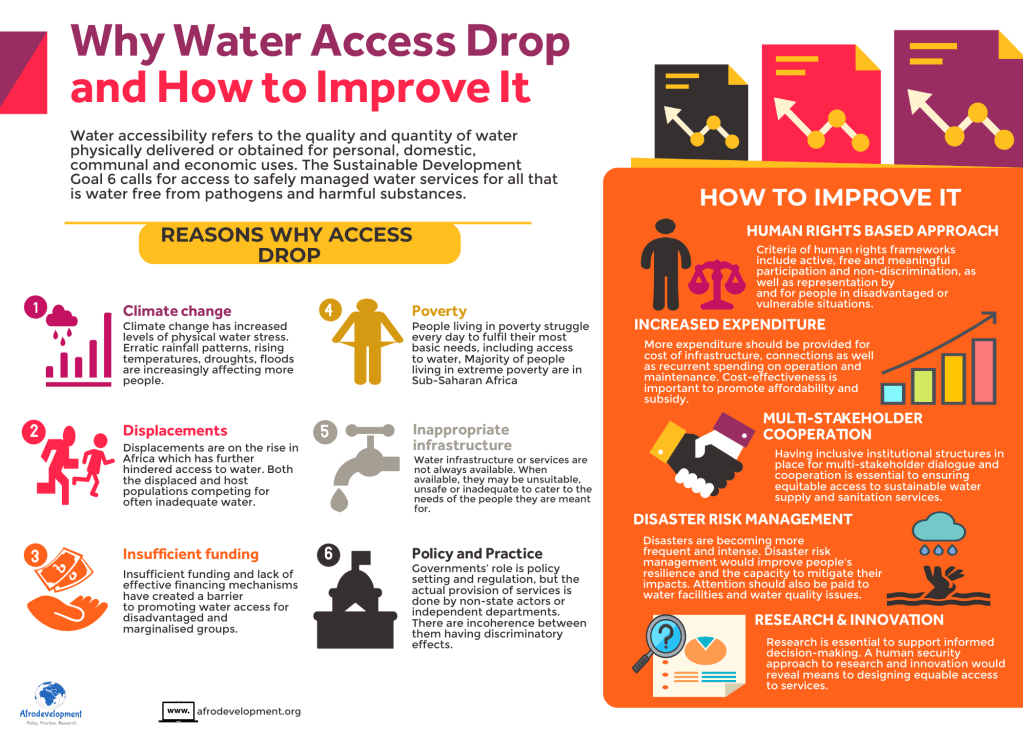

One of the main uses of water for people and households is drinking and have huge impacts on human survival and health. There should be an assessment of the causes of the reduction in water access before suggesting appropriate policy and practice responses. Such assessment must concern what this means for people in different settings including urban, rural, displaced persons camps. Across these settings, six major factors are contributing to low access to safe drinking water.

Climate change has increased levels of physical water stress. Erratic rainfall patterns, rising temperatures, droughts, and floods are increasingly affecting more people irrespective of their location or settlement type. Such hazards are projected to increase in frequency and intensity as a result of climate change. Conflicts have also been predicted to possibly occur due to water scarcity generated by climate change in countries like Mali and Nigeria.

Sub-sahara Africa is currently witnessing its largest forced migration in history. From state internal crises as we have it in South Sudan to regional conflicts like in the Horn of Africa, more people are on the move now than at any time in the past. Even where available, host community and displaced population will compete for access to water which is often inadequate and unsafe.

From state internal crises as we have it in South Sudan to regional crises like in the Horn of Africa, more people are on the move now than at any time in the past.

Insufficient funding is a problem that has plagued the water sector of sub-Saharan countries for decades. This concerns the government and private service providers lacking effective financial mechanisms for service provision. Service provision goes alongside other financial means like tariff structures, subsidies, and CBT, underscoring the importance of increasing public funding for water. With increasing climate risk, experts are calling on governments to adapt this to their funding.

Poverty in the era of the SDGs must be understood as the deprivation of basic capabilities rather than the lowness of income although this does not mean income is not a reason for deprivation. A package of multidimensional factors go into a condition for an impoverished life and these hinder people’s access to water. It must be noted that many people living in multidimensional poverty live in sub-Saharan Africa where 70 per cent of the population is estimated to be multidimensionally poor.

Water infrastructure is not always available. Urban communities which tend to have more infrastructure compared to other settings suffer decrepit water systems. Even when they are available, they may be unsuitable, unsafe or inadequate to meet people’s needs. Water-related natural hazards, such as floods and droughts damage water supply infrastructure, preventing service to millions of people. Infrastructure for water supply is especially scarce in rural areas than other settings. In fact, some researchers have linked the absence of infrastructure to poverty in the region.

Policies and practices have been noted as having a profound impact on water access and promoting social inequalities. They propagate discrimination which excludes access to service for some segment of the population. Entrenched corruption straddles these two factors and further promote exclusion. Management practices in places where water is available can be poor producing inefficiency.

The problems facing access to drinking water discussed are inexhaustive but represents the leading concerns based on recent trends. In addressing these difficulties, a few initiatives have been identified:

Rights-based approach: One such is a human rights-based approach. Aside from prioritising legal and institutional obligations, meaningful participation of the people and principles of non-discrimination must be acknowledged and applied. We come back again to the perspective of capabilities which proposes that all sections of the society have their water needs fulfiled. This is important for social justice and correcting inequalities.

Increased expenditure: It is incumbent upon national governments to drastically increase funding to the water sector. Research has shown that the current levels of funding towards water among many sub-Saharan governmments are below the capital cost required to meet the SDGs. Including considerations of cost of operations and maintenance, subsidies should also be actively incorporated in budgetary allocations for those who cannot afford it.

Multistakeholder cooperation: Institutional structures for the water sector must be clearly defined and multistakeholder dialogue and cooperation prioritised. This is crucial to good governance where institutions not only serve to ensure accountability in fulfiling their respective mandates but also coordinate in programmes and project interventions.

Disaster risk management: About 90 per cent of all natural disasters are water-related especially floods and drought. Flooding damage water infrastructure and pollute water sources while drought hinders physical access to it. Many sub-Saharan African countries have yet to establish and incorporate early warning system mechanisms into their water sectors. Without improved social infrastructure and governance, merely creating disaster risk management mechanisms will not mitigate the short and long term impact of disasters on water.

Research and innovation: More policy-oriented research are needed to support informed decision making. Since the focus of the SDGs includes addressing inequities, more research is needed on groups and individuals who live in vulnerable situations. These research would yield technical innovation as well as the design of models that assesses the multilevel and multidimensional factors that go into water access.

Bolaji Ogunfemi is the Administrator of Afrodevelopment. He can be reached on b.ogunfemi@afrodevelopment.org or on Twitter @BolajiOgunfemi.