Bolaji Ogunfemi

Sanitation is one of the most intractable development challenges of the twenty-first century. It has garnered greater attention from the UN, development actors, policymakers, national governments and donors since the declaration of the Millennium Development Goals in 2000. With the launching of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development in 2015, rhetoric on sanitation discourse has now turned to three overarching sector goals; ending open defecation, universal access to basic services; and progress towards safely managed services.

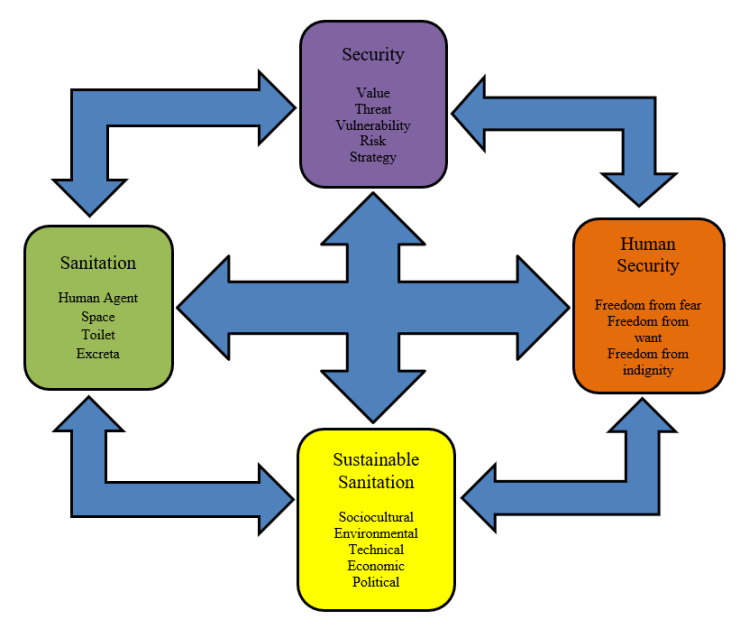

The signs of the time indicate that a model is required to facilitate scientifically insightful description and explanation of the phenomenon both of which are critical to improving theory and practice. Models utilise concepts and inferences to achieve an understanding of the world through symbols that enable scientists to communicate their thoughts to and receive from others. Often, they are named based on an analogy between the major system it describes – here sanitation, and another different system – here security.

The four key propositions guiding the model are that; sanitation directly impacts human security, sanitation indirectly impacts human security through security, sanitation indirectly impacts human security through sustainable sanitation and, sanitation impacts human security through both security and sustainable sanitation. The model asks a basic question; how and why does sanitation generate or deprive certain freedoms in a context?

In order to see what models do, and how they can teach us things, we have to understand the details of their construction and usage.

Sanitation security model

Sanitation security model

Sanitation being a human activity, human agent can be described as the capacity of a human being or person to act in whichever manner drawing on his abilities, knowledge, cognition, values and behaviour within his ever-changing social milieu.

Space is about the physical, sensorial and cognitive relations between humans’ embodiment and surroundings and the idea that certain things or some events belongs somewhere or somehow in particular at a time. It is composed of territory, place and time. Toilet or latrine are artefacts and manifests as the technology aspect of sanitation.

The excreta aspect concerns excreta disposal measures as well as secondary order management stages of containment, transportation, treatment, and disposal or re-use.

Value is the root component of security and relating this to sanitation, they refer not only to the standards that uphold defecation practices of a people or society but also their worldview towards norms attached to excreta management. Sources of threats can be assessed based on types (sociocultural, environmental, technical, economic and political or direct or indirect), level, frequency, timing and severity. They cannot be definitive as they vary depending on the context.

Vulnerability is human or system susceptibility to harm due to inherent weakness in relation to factors that threaten the value. Sanitation related vulnerability originates from three broad categories; chronic (related to basic needs), contextual (arising from social, economic and political processes and contexts of human life like age, gender, social engagement, built and natural environment) and extreme (concerning armed conflicts and natural disasters) which are all interrelated and interdependent.

It is when vulnerable people or systems are unable to mitigate and/or adapt to the threats to specified values and the ineffectiveness of their response options that they become termed as being ‘at risk’ or ‘risky’ therefore necessitating some form of external assistance.

Strategies adopted in addressing risks can be grouped into ex ante (preventive strategies) and ex-post (adaptation and mitigation). While the former is used to refer to measures adopted to prevent a risky event from happening exercised at the individual, collective and governing levels or ensemble, the latter concerns the actions taken to deal with experienced losses after the risk event has occurred with the purpose of minimising effects of losses and facilitate recovery.

Adaptation refers to the exploration of new practices and functions of reducing risk due to changes in social and environmental processes and occurs at the individual and collective levels. Mitigation is enshrined in policies, programmes and approaches of governing institutions.

The next phase of sustainable sanitation involves the sociocultural, environmental, technical, economic, and political dimensions consulted in assessing which means will best provide sustainability in a context. It can be adopted either as a preventive or an adaptation/mitigation strategy at the communal and governing levels.

Human security can be said to be the outcome of the sanitation security model with sanitation, security and human security as contributing factors. In other words, security and sustainable sanitation function as intermediate predictors of how and why sanitation impacts human security.

Freedom from fear is to be free from acts of fear of physical aggression or threat to bodily integrity regarding sanitation related activities. Sanitation should be able to facilitate people’s access to human basic needs like food, water, shelter, health, and education and other related constructs which the customs of a country renders it indecent for people to be without. Freedom from indignity concerns absence of fear that an individual or collectives’ dignity will be attacked. This is a tricky because what constitutes dignity cannot be locked in a box of global definition but assessed on a culture by culture basis which is globally divergent. Dignity as a concept in sanitation discourse also revolves around human rights.

The sanitation security model has the characteristics of being people-centred, multi-sectoral, comprehensive, context-specific and prevention oriented.

The utility of the model can be broadly classified into two;

• Research: Models serve as an interface between theory and empirics in understanding a phenomenon of the world. This model can be adopted by quantitative, qualitative, mixed method and policy researchers to tease out and connect factors previously thought to be isolated. Researchers can link their own indicators to the variables in explaining aspects of the world to guide formulation of policies or designing of interventions. It also helps to integrate the security-humanitarian-development sectors and illuminate interconnections or shortcomings in terms of security, governance, international responses and local resources.

• Project management/Policy: Politicians and other decision-makers have to act on the basis of available evidence from sound diagnosis. The model can help in designing sanitation projects and policies differently better from the way it is currently undertaken. A recurring theme in sanitation service delivery and policy has been the patriarchal assumptions of national governments and development or humanitarian planners and implementers about local processes and so-called beneficiaries of development or humanitarian assistance. With the design of seven project management matrices drawn from the model, it seeks to reorient the internal organisation and workings of the sanitation aid and service delivery.

Bolaji Ogunfemi is a PhD student in London. He can be reached @bulgie05 on Twitter or email b.ogunfemi@afrodevelopment.org.

I really like your blog.. very nice colors & theme. Did you create this website yourself or did you hire someone to do it for you? Plz respond as I’m looking to create my own blog and would like to know where u got this from. thanks a lot

LikeLike